When filmmaker Greg Campbell was 14 years old in Fayetteville, North Carolina, he met in his high school English class somebody who would become one of his dearest friends. “It was pretty clear that we were cut from the same cloth,” Campbell remembers.

It would be in a hotel lobby in Benghazi, Libya, almost 30 years later, where Campbell would see his friend for the last time.

Chris Hondros, an American photojournalist, was killed April 20, 2011, by a mortar blast in the Libyan city of Misrata. He was on assignment for Getty Images, and his death came just one week after he had said what turned out to be his last words to Campbell: “We got you out of here unscathed.”

But in Campbell’s documentary, “Hondros,” he shows that the physical absence of his friend has not meant an obliterated presence, a presence never to be seen or felt again.

“There’s an instinct that I’ve got that parts of him are still out there somewhere, that parts of him can be found in the people and the places that were important to him,” Campbell says in the film.

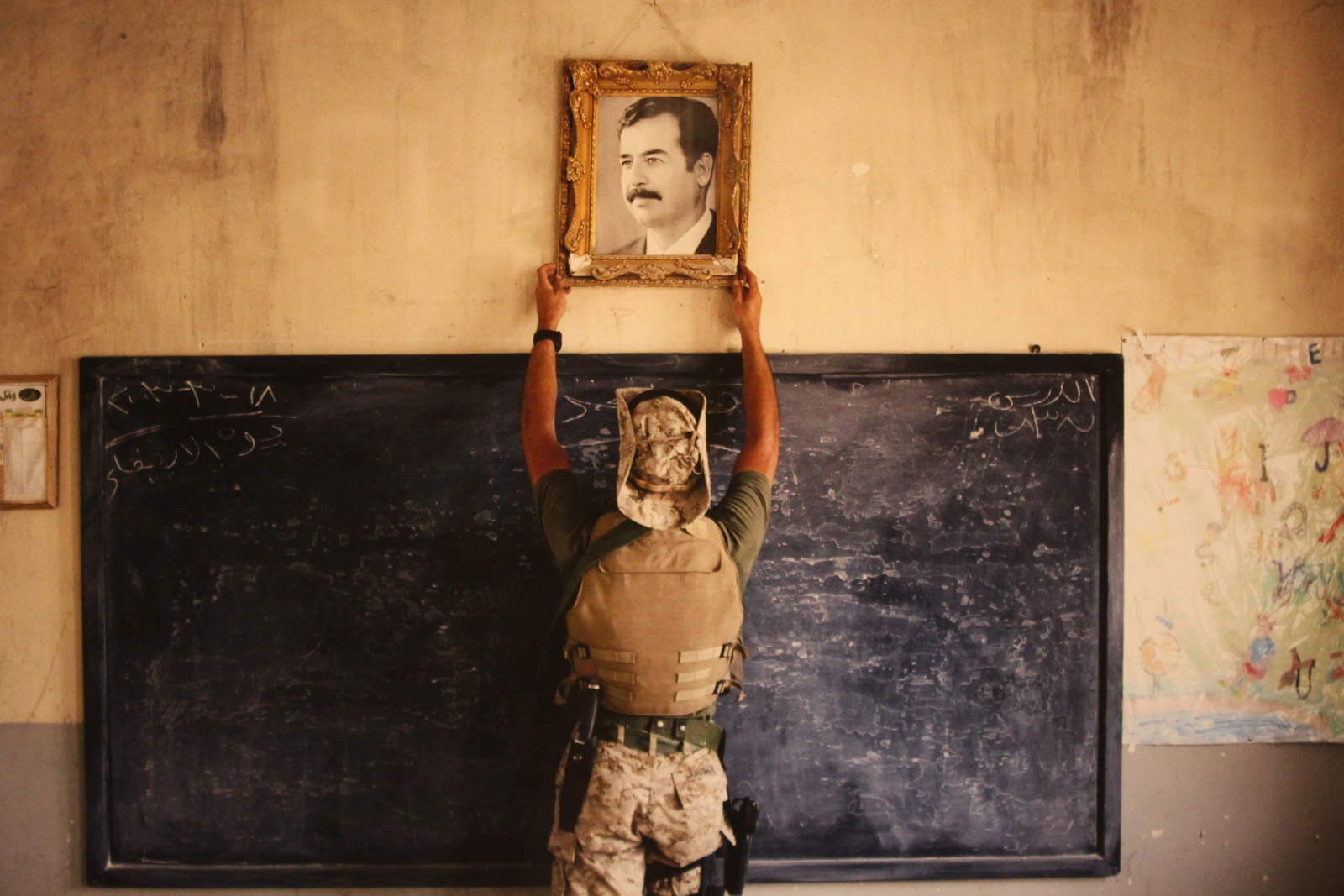

Hondros’ career as a photojournalist began with the war in Kosovo in 1999. Since then, he remained dedicated to covering conflict around the world, setting foot in Liberia during the second civil war and Iraq during and after the US invasion.

“I think one of the greatest surprises, and one of the most rewarding things about doing the film, was learning about just how deeply Chris affected other people,” Campbell said.

In July 2003, Hondros photographed a Liberian government soldier who had just fired a rocket-propelled grenade from a contested bridge in Monrovia. In the image of Joseph Duo, seen below, Hondros captured what at first glance seems simply like one young man’s moment of jubilation and celebration — until you come to the realization that it was born on the front lines of a yearslong civil war.

Hondros didn’t get Duo’s name at the time. About two years later, though, he returned to Liberia and made sure to meet him. Hondros not only learned who Duo was, he also paid for him to attend school again. Duo, having become a child soldier at the age of 14, had only received an education up to the 10th grade.

“The idea for the film kind of originated with Joseph Duo,” Campbell said. “Joseph contacted me on Facebook, this was not long after Chris was killed. He just was reaching out to express his condolences and to share the feelings that he had around the event that took Chris’ life. It occurred to me that he knows Chris in a way that is different from the way that I knew him.”

In January 2005, Hondros went to Tal Afar, Iraq, during the Iraq War. There, he photographed a little girl named Samar Hassan, whose parents were shot to death by US soldiers during a late afternoon patrol.

In the image of Samar, she is screaming, the red flowers on her dress matching the red blood on her face and on her hands. It’s a sight that once seen, will likely never be forgotten. Especially not by Samar, who was only 5 years old when she witnessed bullets riddle her parents’ bodies.

“One of the things that we sought to do in the film, to sort of expand out from the moments surrounding when that photograph was taken, was to show some of the inherent gray area that Chris operated in and people who do this profession are required to navigate,” Campbell said.

“And it can be extremely difficult. The situation cries out for somebody to blame, whether it’s the US soldiers, or it’s the parents driving the car and not heeding the warning shots, to just having been out after the curfew had already descended. …

“The implications of the things that occurred in that photograph are vast and we really wanted to take our time to explore some of those implications, because I think that that is something that Chris would have insisted upon: us retaining the focus. As much as it’s about him and his life and his legacy, he made his life and his legacy about the people that he was photographing.”

Campbell described Hondros as confident and optimistic. But he was not only optimistic about what he was doing in his own life, Campbell said, he was also optimistic on behalf of his friends and what they wanted to do in their own lives.

“It’s just really easy, I think, sometimes to lose sight that there is a flesh-and-blood person behind the lens who is dedicated to the original ideals of journalism and photojournalism, risking their life to bring these stories, that are important for us to know, onto the front pages and into our consciousness,” Campbell said.

To Campbell, one of the most valuable things about Hondros was his ability to offer clear-headed advice and thinking. What he felt most after Hondros was killed was the absence of a friend with a steadying hand.

“In this particular moment in time that we find ourselves living in, where information is being weaponized, propaganda is ubiquitous now, the value of having a professionally trained photojournalist to be the world’s eyes and ears has never been greater.”

“Hondros,” directed by Greg Campbell, will be in select theaters on Friday, March 2. It will be available via video on demand on Tuesday, March 6, and on Netflix on Sunday, July 1.

source: cnn.com By Benazir Wehelie