From deep inside a Siberian mine, researchers have catalogued a series of materials unlike any others yet found in the ground. They do, however, bear a startling similarity to certain lab-grown materials that weren’t thought to exist in nature at all—until now.

In the last few decades, chemists have been crafting a series of new materials in their labs called metal-organic frameworks, or MOFs. These materials are “molecular sponges,” capable of soaking up gases like hydrogen or carbon dioxide—even storing them for future use, like a cell. A new paper in Science Advances reveals that not only are these materials also found in nature, we’ve had them in our hands for over 70 years. We just didn’t know what they were.

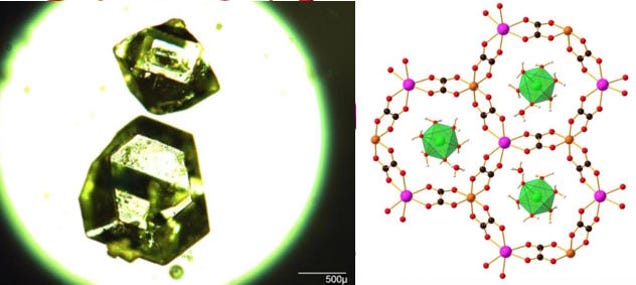

The samples of the two minerals, stepanovite and zhemchuzhnikovite, were originally catalogued by geologists starting in the 1940s after being pulled from mines in Siberia. With the technical limitations of the time, however, their unusual properties went by mostly unnoticed. Then, in 2010, chemistry professor and senior author of today’s paper, Tomislav Friščić of McGill University, came across an account of the samples in an old article in a mineralogy journal. He was struck by certain structural similarities between the minerals and today’s lab-generated MOFs.

With the original samples in Russia unavailable, grad student and first author Igor Huskic, also of McGill, set about creating synthetic versions of the samples using the details from the old mineralogy journal. He was successful and the synthetic versions of the minerals did, indeed, mimic the MOF materials. But it wasn’t until their Russian co-authors tracked down actual samples from decades ago that the team could confirm that finding.

“It’s the opposite of how it’s usually done. Usually what happens is a type of material is discovered in nature, it’s analyzed,” Friščić told Gizmodo, “and then we find it has interesting properties, which we can then mimic in the lab.”

The lab-grown versions of the MOFs have generated considerable excitement among researchers because of their possible applications. Among the potential uses is using them as carbon sequesters for the carbon dioxide we pump out into the atmosphere or even using them to create incredibly-efficient fuel cells. But those applications are still down the road, raising the question of what might have been had we recognized these properties earlier.

“One conclusion I can make is, if it were possible in the ‘40s to perform structural analysis like this, then the whole area of MOFs would have been accelerated by 50 years,” Friščić said.

The conditions in which these samples were found were unusual. The mine in Siberia was 250 meters deep and under a layer of thawing permafrost. So only a very small amount of the samples were collected. Still, Friščić is optimistic that there could be other sources out there—easier to get to and much more more abundant—with similar properties to MOFs.

The next step is to figure out just where similar minerals could be found, and continue to work out just what we might be able to do with both them and their lab-grown equivalents.

source: gizmodo.com by Ria Misra